The room was big and white and dusty and filled with fear.

There was no reason for the fear. It was just something she felt as she entered the room. She’d felt it the first time that she’d walked through the door. She’d turned the round, loose, rattly old doorknob, and rested her hand on the much-painted door frame, and put her head into the room, and she’d been scared and she didn’t know why.

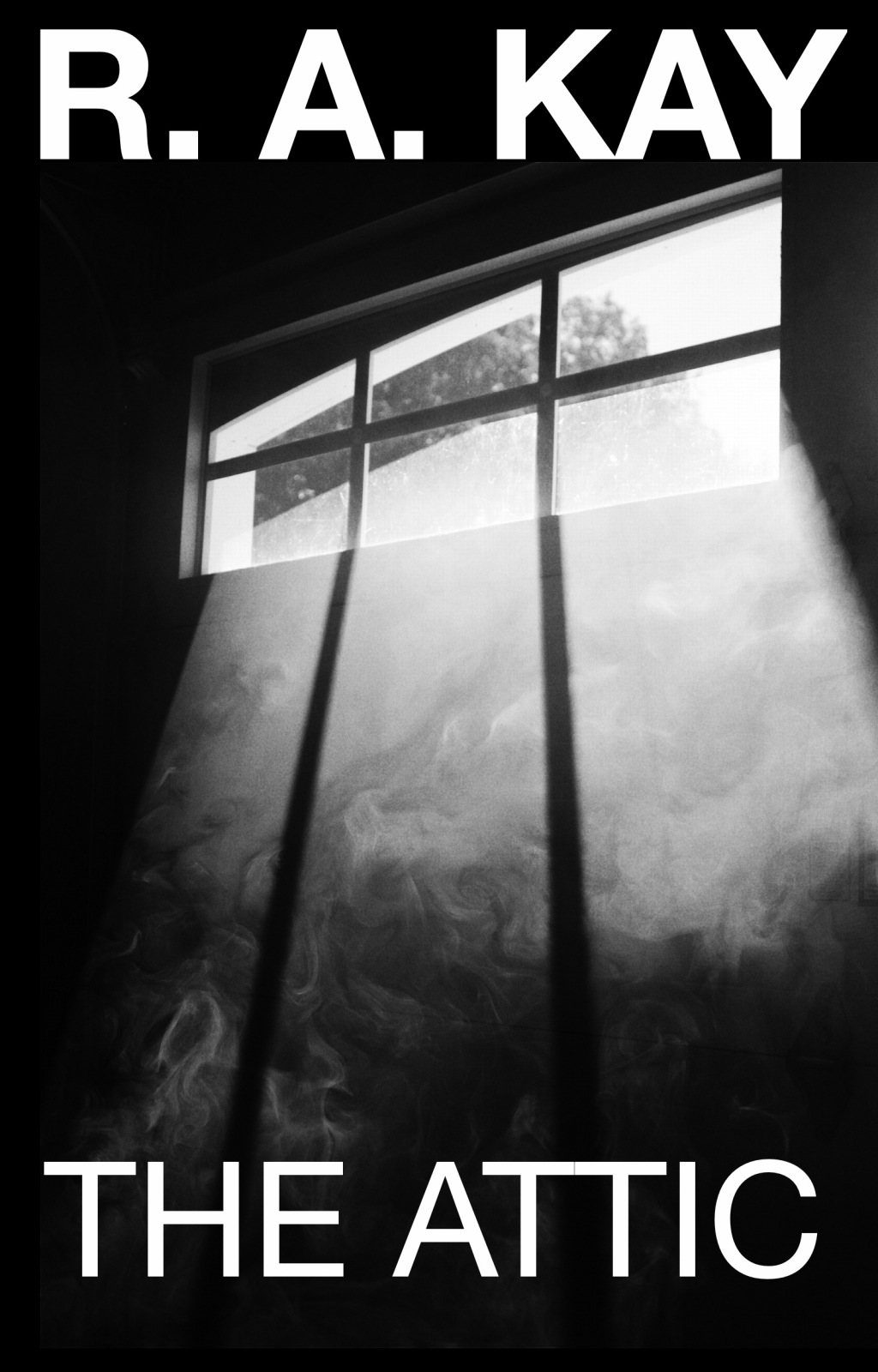

It was the top room of the house, a big attic room, empty and bare of any furniture, just dusty floorboards and white-painted wood-chip covering the walls. A large dormer window had been installed at some time, its un-curtained panes streaked with grime on the inside and a splatter of birdlime on the outside. Two great, thick timber purlins ran along the length of the room, one on each side, the ends embedded in the brickwork of the walls that supported the roof. It was a light, bright room, almost too bright; when the sun shone from the west, it poured in through the window and bounced off every surface, each reflection accumulating and magnifying the light until it became almost painful to the eye.

Her husband squeezed past her and walked through the door. The sound of his leather-soled shoes on the bare floorboards echoed around the room and made her feel uncomfortable, as if he was somehow intruding. She followed him in, her rubber-soled sneakers making no sound at all.

“Yeah, this could be great, Jo,” he said. “Nice and bright. Bags of room. Wall space for hanging your work, and that area under the dormer would be ideal for your desk and easel and whatnot. A fair old view, too, although a titch like you’d need a step up to see it, and these windows will want cleaning, but it all looks good to me. Just what you said you wanted, really. Don’t you think, Jo?”

He turned to her and saw that she wasn’t looking at the room. She was looking at him. She was a petite red-head, with blue eyes and high cheekbones, and lips that were usually formed into an easy smile. Her lips were pressed tight together right now, though. He saw something in her eyes too, something he didn’t recognise, that he’d never seen before.

He saw that she was scared.

“What’s the matter?” he said.

She stood in the centre of the room, hugging herself, her shoulders hunched up. It was a warm spring day but she looked like she was cold. She shrugged.

“I don’t know,” she said.

He walked over to her and put an arm round her shoulders and kissed her cheek. He made an assumption. It was wrong.

“Bit too late for second thoughts now, love. We’re in. This is it. Day one of life in our forever home.”

He kissed her again, smiling. She didn’t respond. A frown spread over his face.

“Come on, Jo. What’s up?”

She shrugged again. “I don’t know, Mark.”

“Is it just because it needs cleaning and decorating? We can sort that out, can’t we? A lick of paint and it’ll be fine. Won’t it?”

Jo slipped out of his arms and began walking around the room. She ran a hand along one of the timber purlins and then rubbed the acquired dust off with her other hand. She paused at the window, standing on tiptoe to see out through it. At the end of the room she stopped in front of the wall. Mark walked up to stand beside her.

“Wood-chip,” he said, running his hand over the heavily painted surface of the wallpaper. “Hate the bloody stuff. Reminds me of when I was young and we lived in that godawful terraced house. Tiny little place it was, too small for a family as big as ours. I hated it. I suppose that’s why I’ve always wanted somewhere like this; a big, old house, with lots of rooms and nooks and crannies, lots of space to spread out in. Lots to love.”

He reached out to a small piece of torn wallpaper that had been left trailing down. He tugged at it and the tear became bigger.

“Well, that’s handy,” he said. “Whoever put this paper on was a bit stingy with the paste. Looks like it’s only held on by the paint now.”

He tugged again. The paper peeled easily away from the wall. Long strips of it dropped to the floor, the layers of paint that had covered the paper crumbling to dust as they fell.

“We could have this lot all off in an couple of hours, Jo. Put something nice up instead. Or we could get the walls skimmed and paint them some bright, happy colours, yellow or orange or…”

“Mark,” said Jo.

Mark looked at his wife. She was staring at the bare plaster that had been hidden beneath the wallpaper and was now revealed to them for the first time. He stepped back and stood alongside her and tried to see what she was looking at. He couldn’t see anything except for scraps of wallpaper and a few scratches on the wall.

“What is it, love?”

“Look,” she said. “Can’t you see?”

Mark looked again at the area of the wall that Jo was pointing towards. He saw that the scratches in the plaster weren’t random. They had been scribed into the surface with a fine pointed tool of some kind, the point of a knife, perhaps, or a nail. He could see that the lines were part of a drawing. The style looked like something scratched out by a childish hand; odd-angled lines and curves had been formed from multiple passes with the tool, scratching and re-scratching, so that the resulting shapes had an indeterminate, feathered appearance. The shapes were of children, of boys and girls of different ages and sizes and shapes.

They were naked.

The two of them stood together in silence looking at the figures. The detail was enough for them to know that they were drawn from life, by someone who had seen these figures unclothed and had who had observed them closely. They could see three figures, two girls and a boy. The feet of each figure almost rested on the skirting board. They appeared to be drawn to scale; life-size.

The tallest figure was that of a girl. She stood in profile. The boy stood with his back to this figure, and a smaller girl stood on the other side of him, facing into the room. No emotion could be seen on any of the faces. None of them were smiling.

“We can’t stay here,” said Jo.

Mark said nothing.

“Mark,” said Jo. “We can’t stay here. I can’t stay here.”

Mark turned to face his wife.

“Let’s just calm down a minute,” he said. “There might be a perfectly sensible explanation for all this.”

“Like what?”

Mark shook his head. “I don’t know, Jo.” An idea struck him. “Maybe the kids drew themselves. Maybe they were naturists or something, the family that lived here when this… was done. Maybe they were just… artists. With really bad taste.”

“I’m not living here,” said Jo.

“D’you think you’re just being a bit emotional, maybe?”

“I’m not.”

“We’ve only just moved in, Jo,” shouted Mark. “This is our first day. The removal van hasn’t even left the drive yet. We can’t just pack everything up and leave. We couldn’t if we wanted to. It would take months to sell now, and all our money is here, in the bricks and mortar of this house. We can’t afford to live anywhere else.”

Jo turned to look at the figures on the wall again. She looked at the unsmiling face of the small girl and tried to imagine what she had seen, what she had done. What had been done to her.

“I don’t care,” she said. “I’m not living here, Mark. I can’t.”

Jo lay in bed, staring at the ceiling of the room as Mark snored gently beside her. It was the early hours of the morning but she hadn’t slept. She had laid down and looked up and realised that their bedroom was directly below the attic room and all possibility of sleep had left her. All she had been able to do was to think about the drawings. She had tried to believe Mark, to believe that there was an explanation that didn’t include all the horrors that still floated around in her mind, but she couldn’t. For each possible explanation that he conceived, she conjured a more probable rebuttal until she knew, she absolutely knew, that whatever had happened in that room had been bad beyond her imaginings.

As she lay there she wondered how these unknown children must have felt. She refused to consider the physicality of what might have been done to them. It seemed to her that thinking about such things only made them worse and there was nothing anyone could do now that would ease any pain they had suffered. She thought instead about their lives. Had any part of it been good, she wondered, or did they live in misery from the day they were born? She hoped that they had been able to enjoy some good days in their brief lives.

She sat up.

Brief lives? How do I know that they’re dead? Perhaps they aren’t. Perhaps they’re still alive. Maybe they survived and managed to overcome their past. Maybe they even managed to live well in spite of it.

The idea that there could yet be some hope for the children made her restless. She slipped out of bed and put on her dressing gown and slippers and headed for the kitchen. As she reached the top of the stairs another thought struck her. If there was any information still to be found about the children, about how they might be found if they were still alive today, it was likely to be scrawled on the walls of the attic.

The attic door creaked as she opened it, and she felt the sense of fear again as she stepped onto the bare boards. Light from a full summer moon hanging just outside the window filled the white-painted room but still she tried the old brass switch. There was no bulb in the socket that dangled from the centre of the roof. She paused for a moment, listening. The only sounds she could hear were a gentle breeze running over the roof and, in the far distance, the noise of traffic on the bypass.

Walking slowly, treading carefully, she moved across the room. The drawings could still be seen, even in this light. They seemed to be more clearly defined, if anything, the angle of the moonlight across the drawings providing a relief effect. She bent to examine the figure of the tall girl. There were no other markings that she could see, no words or messages, just the feathery scratchings that outlined the figure. She moved on to the figure of the boy.

He was looking at her.

Jo staggered backwards. A slipper fell from her foot and she stumbled and sat down heavily on the bare floorboards. The dull thud as she hit the floor echoed around the room.

The figure of the boy was facing her.

He hadn’t been like that before, she was sure of that. He’d been standing sideways, facing the small girl. He was facing out into the room now though, looking at Jo, his eyes big and round, his mouth unsmiling. Jo scurried away from him, moving backwards on her hands and feet. She bumped into a pair of legs and screeched.

“Jo,” said Mark, lifting her up to him. “What’re you doing?”

She grabbed hold of his arm and pointed to the drawings. “He’s looking at me, Mark. See? The boy’s looking at me.”

Mark followed the line of her finger. A cloud passed over the face of the moon and the room dimmed for a moment. When the light returned he walked over to the wall. He knelt down and examined the figure of the boy and then stood up again and moved to one side.

The boy was facing the little girl.

Mark shrugged and opened his hands. He walked back to her and put his arms round her.

“Maybe it was a trick of the light, love,” he said. “You can’t really see anything properly in this gloom. I’ll put a bulb in tomorrow. What were you doing up here anyway, though?”

Jo stared at the wall.

“I thought I might find something,” she said. “Some more details. About them. I wanted to find out who they were. I wanted to help them.”

“Help them?” said Mark. “How would you do that? That wallpaper’s been on for bloody years, decades probably. These kids would be well and truly grown up by now. They’d be old people, maybe even dead. How could you help them?”

Jo shook her head.

“I don’t know,” she said. “But they do need help. I know that. I can feel it.”

She waved as Mark drove away the following morning. He had meetings with the estate agents and solicitors to finalise the bills for the house move, and then he’d arranged to see their accountant to see what options they had if they did have to move again. Jo had intended to go with him but she had hardly slept and wasn’t feeling up to it. The bathroom mirror showed her how tired she looked. Even the dragonfly tattooed on her shoulder seemed limp and lifeless. She had a shower, rinsing off with the water set as cold as she could stand it in an effort to liven herself up. She made a large pot of strong coffee and drank it with some toast and honey. The tiredness lifted and she began to feel more like her usual self, so she started unpacking the boxes that had been stacked in the living room and distributing the contents around the house. Whatever happened, they were going to have to live here for a while, after all.

It was a grey day outside and the rain came, light at first, but then heavier and heavier, along with a wind that gusted all around the house and blew shrill whistles through the gaps that it found around the doors and windows. She carried boxes full of pots and pans and cutlery through to the kitchen; boxes full of paintings and photographs and ornaments to the dining room; suitcases full of clothes and shoes up to the bedrooms. She took some vases into the conservatory at the back of the house and stood and watched the rain hurl itself against the old glass panes. The trees and bushes in the garden jumped and threw themselves around, and the clouds above them ran through the sky like a wild, grey river. She began to feel cold and tired again. I need to sleep, she thought. She went upstairs and lay on top of the bed and closed her eyes. She was immediately asleep.

She dreamed of fear that night. Everything that had ever scared her came to to visit her in her sleep: she was running from the great, tall, blonde plastic dolls whose legs never moved but who came closer and closer with every frantic gasp as she ran on legs that were weighted like lead; she was falling from the rigging of the pirate ship into the fathomless green sea, drowning in it, the cold of it, the weight of it, pressing on her, taking her last breath; she was in her bed and the growling thing was there, the thing that moved when you weren’t looking, that came closer every time she looked at it and failed to see it. And then her mother was there, and then she wasn’t, and her father, and then neither of them were there, neither of them had ever been there, and she was alone she had always been alone, she would always be alone, forever and forever and forever.

A crash of thunder brought her immediately awake.

She sat upright on the bed, sweating, breathless, her body tense and shivering, waking from the nightmare. The thunder must have broken right on top of the house, she thought. She stayed there, listening for more, but nothing came and she calmed herself with regular, steady breaths. She eased herself off the bed and stretched and then walked to the bedroom window. It was late afternoon. Outside, the rain was still coming down in great billowing silver sheets. Mark’s car was still missing. She looked at her watch and was surprised to see that she had been asleep for less than an hour.

There was a rumble above her head.

She looked up at the ceiling, her senses completely focused on the space above her now. She didn’t hear the wind or the rain or the ticks and clicks of the house. She heard only the silence of the attic.

She pushed the attic door open slowly, looking into the empty space of the room from the landing outside. The bare boards and white walls and the rain-drizzled window were all that she could see. She noticed that the rain had almost completely washed away the streak of bird-dropping that had been splashed across the window and she felt oddly comforted by that, by the mundane normality of that fact. It was just a window. This was just a room. They were just drawings.

She stepped into the room.

The rain kept coming, millions of drops hitting the house in irregular whippings as the wind drove it against the tiles and the windows and the walls of the building. There were no other sounds, nothing, apart from the soft creak of the floorboards as she slowly crossed the room. She stopped in front of the drawings.

They were as they had last seen them, the tall girl looking at the boy, who looked at the small girl, who looked out into the room. Jo felt her heart begin to hurt, as though sadness radiated out from the drawings and seeped into her. She knelt down in front of them.

“Who are you?” she murmured. “Where are you now? What happened here?”

She ran her hand across the bare plaster around the figure of the little girl. Her fingers picked up a thin film of dust. As she bent to blow it off she saw something behind a piece of wallpaper that had begun to peel away under its own weight. She pulled the paper down, and, slowly and carefully, she revealed another figure. It was another small girl. This figure was facing forward but looking to her right, towards the other small girl. She was reaching out to her, one hand suspended in mid air, inches away from her friend.

She was crying.

Jo felt the tears form in her own eyes. She felt them tickle as they ran slowly down her face. The tears fell from her cheeks and made dark round stains on the wooden floor as she cried. She began to pull away the wallpaper from the wall beside this new small girl, ripping carefully but dropping the torn paper in thoughtless piles on the floor, each dropped piece stirring a flurry of dust, and more dust, until the room was filled with a smokey haze.

She found another little boy.

She found another tall girl.

And in the arms of this new tall girl she found a baby.

Jo was sobbing now. Six children, seven with the baby, up here in the attic. Had they all lived up here? How long for? Had this been all they knew? Had this room been their entire world?

Who could do such a thing?

She covered her face and turned her back on the figures, unable to look at them any longer. Rubbing the tears away, she opened her eyes and saw the wall at the other end of the room.

It was painted white, and covered with woodchip wallpaper.

As she walked towards it, Jo thought she heard a sound behind her. She turned back to face the stripped wall. The figures were as they had been. From this end of the room, the scene looked like a tableau, a wall painting from a time long ago. For some reason she thought of the Last Supper. She turned back to the opposite wall and, as she did, she thought she saw something move. She persuaded herself that it was her imagination, that she hadn’t seen anything. This time she didn’t turn back.

The paper on the opposite side of the room was more firmly stuck to the wall but still it came away fairly easily. She started on the right side and stripped it off in small tears, leaving the bits that wouldn’t come for another time. She pulled and tore, methodically and patiently, exposing more and more plaster, revealing almost half of the wall, but finding nothing like the drawings opposite. She paused for a moment to rub the dust off her hands and her face. As she reached up to pull the next piece, she heard a gasp and turned her head.

Behind her, all the children were facing forward.

Jo moaned and turned to face them, a piece of paper still in her hand, her back against the wall that she had stripped.

Nothing happened.

The children stood there, unmoving.

Jo began to move towards the door. She was trembling with the fear that she had first felt in that room, a fear that she could feel radiating from the children like heat. She reached the edge of the door. A car door slammed outside. As she moved to go around the open door, Jo glanced at the wall opposite the children.

Where she had been working, where she had torn down that last big strip of wallpaper, a face had been etched into the plaster. The face was big and round, with a curved moustache and topped with short, bristled hair. And there were spectacles. Round, wire-frame spectacles, covering small, bright eyes. She was being watched. More than that, she was being examined. The eyes weren’t just looking at her, they were looking into her, seeing what she was, what she had been, what she had done. Seeing past the woman to the girl. To the child.

Mark came running up the stairs shouting her name. He walked into the room smiling.

“I thought you’d be up here somehow,” he said. “Jo?”

He looked around the room. Paper was strewn all over the floor. He saw the newly revealed children and he went over to inspect them. He traced the outline of the baby with his forefinger. As he turned to leave he saw the opposite wall. He walked up and examined the face of the spectacled man. Mark pulled off more of the the paper below the face, the paper peeling away in big, easy strips. The drawing was in the same feathery style as the drawings of the children and was again life-size, although the man wasn’t tall. He was wearing a long coat over a jacket and and trousers and a waistcoat. He had a walking cane in one hand.

“Jo,” shouted Mark. “Are you here? You should see this. Jo?”

Mark looked again at the face of the man. The mouth beneath the moustache seemed to be smiling.

“Did you get away with it, I wonder?” he said. “I bet you did, didn’t you? You dirty old bastard.”

Mark placed his hand over the face and began to rub. The loose plaster and old wallpaper sizing rubbed easily into the scratches of the drawing. The sneer, and the face that carried it, began to fade.

“I’m going to rub you away, you shit,” said Mark. “I’m going to wipe you out.”

He stepped back to look at what he’d done. The figure of the spectacled man was becoming vague and indistinct and Mark smiled at his small victory. As he stood there he saw that only half of this wall had been stripped. He wondered if there were any more drawings hidden beneath the woodchip. He tore another piece of wallpaper away and there, beside the rubbed out man, scratched into the plaster, he saw the dragonfly.

Leave a comment